“Time is running out for Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega,” proclaims a headline in The Economist. “Nicaraguan students whose families fought with Daniel Ortega to oust the Somozas now lead a rebellion against Ortega’s own family dynasty,” a sub-head in The Wall Street Journal informs us.

Things are clearly unsettled in the Central American nation. Seeing the name Daniel Ortega back in the news again evokes interesting memories for me. Some of those memories found their way, in a literary guise, into my first novel Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead. If you have read the book, then you know that the narrative does not lead my protagonist Dallas Green to Nicaragua, but it does take him up to and over the Mexico-Guatemala border. Along the way he becomes mixed up with a couple of political activists, one from California and the other from Galway. While those characters are completely invented, the American one (Peter) was at least partly inspired by people I knew in Seattle in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Here’s the background. When I was young and naive, I went to work for a weekly suburban newspaper. What I did not realize until I had been there awhile was that there was a unionization effort well underway by employees in my department. Because I was new and apparently unoffensive to management, I was persuaded to represent the prospective new bargaining unit in labor negotiations. Following a vote to unionize, I was elected the union representative. At this point the boyfriend of a co-worker latched onto me, convinced that I was some sort of firebrand of the workers’ rebellion. This fellow was an unabashed political leftist keen to find foot soldiers for his various projects. One such project was reading international news items with a non-American, non-corporate slant five evenings a week on a non-profit, community-based radio station, Seattle’s legendary KRAB. An even more interesting project my friend got me involved in was a voluntary technical effort to help modernize the Nicaraguan banking system. No, really.

In 1979 Sandinista rebels had overthrown the Somoza dictatorship and established a revolutionary government. A member of the new ruling junta was Daniel Ortega, the same man who is now Nicaragua’s president and who is currently facing mass student-led rebellion in response to cutbacks necessitated by the government’s financial mismanagement. According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, at least 127 people have been killed and 1,000 injured in the crack-down on anti-government protests that began in April. Four decades ago, though, Ortega was one of the young revolutionaries who had found themselves newly in charge of their country. One of the many challenges they faced was an antiquated banking system in which remote branches could not efficiently communicate with the capital Managua. That was what I got drafted for. The fact that I was learning to program at work and knew Spanish from having lived in Chile made me an near-ideal candidate.

While the Reagan administration was supporting Contra rebels to undermine the Sandinistas, I was writing code—and others were playing with shortwave radios—to build a packet-based transmission system to bypass Nicaragua’s lack of wired infrastructure. Personally, I looked at it more as a technical challenge than a political cause. The work we did was passed on to other volunteers, who took it to Nicaragua. I have no idea how much, if any, ended up being used in any practical way down there. One volunteer I met briefly along the way went down to build a rural hydroelectric facility. Unfortunately, it was located in the northern Contra war zone, and he was killed in an ambush at the age of 27. Enthusiasm for our project was already on the wane even before the Sandinistas were thrown out of government in an election in 1990.

The story in Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead takes place several years before I had any (long-distance) involvement of my own in Central American politics, but my experiences in the 1980s—along with campus politics during my university days—were good research into how the American leftist mind works. While there may have been some wry hindsight humor in the way I portrayed Peter and Séamus, I hope I was fair to their point of view. The older and more cynical I get, though, the more I tend to think that revolutions are not really about ideology at all. In practice, by my observation anyway, revolutionaries are ultimately less concerned with the actual order of the social hierarchy than whether the right people are at the top.

Still, those who roll up their sleeves and get involved in the trenches deserve a certain amount of respect. The fates of Charles Horman in Chile in 1973 (subject of the Costa-Gavras film Missing) and Ben Linder in Nicaragua in 1987 are stark reminders that idealistic activism is not without its risks. As you may have guessed, they were both inspirations for my character Tommy Dowd, who meets a similar fate in my fiction.

Books available for purchase at Afranor Books on Bookshop.org and from Amazon and other major online booksellers

(If you are viewing this on a phone, you can see many more links to sellers by switching to this site's desktop version)

My Books

“I actually could not put the book down. It is well written and kept my interest. I want more from this author.”

Reader review of Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead on Amazon.com

All books available in paperback from Afranor Books on Bookshop.org.

Wednesday, June 13, 2018

Thursday, May 17, 2018

Mud in Your Eye

On my movie blog I like to joke that I write my film reviews and commentaries—especially the ones dealing with the Academy Awards—while drunk. I am sure some (most?) readers believe it is true, not least because of the quality of the writing or the frequency of typos. I am sure that my latest commentary, which discussed how UK drink driving laws were threatening the closure of a film landmark in northern Scotland, did nothing to dispel the notion.

The image of the dipsomaniac writer is well ingrained in the popular view of authors. Ernest Hemingway, for example, was known to be a prodigious drinker, and it is difficult not to notice that novels like The Sun Also Rises seem to be chronicles of one drinking session after another. Indeed the number of celebrated writers who had reputations as serial imbibers, if not full-blown alcoholics, includes such renowned figures as F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, William Faulkner, Truman Capote, Edgar Allen Poe, Dorothy Parker, Dylan Thomas and Tennessee Williams. The list goes on and on, and never mind the ones truly legendary for their exploits in substance abuse like Charles Bukowski and Hunter S. Thompson.

There are so many great talents who apparently drank all the time that one wonders whether or not it is entirely coincidental. Is it possible that alcohol can actually unleash one’s creative potential? It is a thesis I have willing to test. Especially since my wife gave me the generous gift last Christmas of a very dear Irish whiskey called Writer’s Tears. Can there be a better name for a bottle of spirits? Unfortunately, it was pricey enough that I have been hesitant to drink very much of it. Perhaps at some moment when I am truly in need of inspiration?

It turns out that someone has actually conducted a study into this. Believe it or not, the Harvard Business Review recently published an article with the definitive headline “Drunk People Are Better at Creative Problem Solving.” There you are. Case closed.

The online version of the article by Alison Beard sums it up in the very first paragraph: “Professor Andrew Jarosz of Mississippi State University and colleagues served vodka-cranberry cocktails to 20 male subjects until their blood alcohol levels neared legal intoxication and then gave each a series of word association problems to solve. Not only did those who imbibed give more correct answers than a sober control group performing the same task, but they also arrived at solutions more quickly. The conclusion: drunk people are better at creative problem solving.”

This immediately raises two questions: 1) was this some sort of April Fool joke, and 2) where can you sign up to take part in a study like this? Professor Jarosz elaborates: “You often hear of great writers, artists, and composers who claim that alcohol enhanced their creativity, or people who say their ideas are better after a few drinks. We wanted to see if we could find evidence to back that up, and though this was a small experiment, we did.” Asked if this means all people in creative jobs should be drinking more, he replies, “Very few professions require you to be 100% thinking outside the box or 100% focused, so I think it’s going to depend on the task you’re doing. You know the old saying ‘Write drunk, edit sober’? Well, there’s a reason the ‘edit’ part is in there.”

There’s the rub. I do not doubt that a certain amount of inebriation can have a positive effect on the creative process for the same reason it can make people feel more relaxed and confident in a potentially stressful situation. Alcohol lowers inhibitions and that can be very liberating emotionally and mentally. I suppose it helps bring out thoughts and ideas that are partially suppressed. Experience, however, suggests that drinking is a disaster when it comes to doing anything that requires concentration, consistency or a quick reaction time. Things that sound brilliant when you are a bit tipsy can be excruciatingly embarrassing when replayed to a sober audience. If you think finding and correcting mistakes—let alone avoiding them in the first place—is difficult under normal circumstances, well, it becomes pretty much impossible if you have been partying in your office.

Professor Jarosz, who describes himself as a craft beer fan, also reports coming across research showing that, surprisingly, people who have been drinking speak with more fluency in a foreign language. I can personally vouch for that, although I have never been sure if a bit of pisco or tequila only makes me think I can speak Spanish better.

In the end, this study strikes me as so many academic reports I read about. After all the research and study, the conclusions always seem to me to have been obvious from the outset. Case in point: “One paper, ‘Lost in the Sauce,’ by Michael Sayette at the University of Pittsburgh and coauthors, reported that people under the influence are more susceptible to mind wandering, which could be helpful in some scenarios but harmful in others.”

The image of the dipsomaniac writer is well ingrained in the popular view of authors. Ernest Hemingway, for example, was known to be a prodigious drinker, and it is difficult not to notice that novels like The Sun Also Rises seem to be chronicles of one drinking session after another. Indeed the number of celebrated writers who had reputations as serial imbibers, if not full-blown alcoholics, includes such renowned figures as F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, William Faulkner, Truman Capote, Edgar Allen Poe, Dorothy Parker, Dylan Thomas and Tennessee Williams. The list goes on and on, and never mind the ones truly legendary for their exploits in substance abuse like Charles Bukowski and Hunter S. Thompson.

There are so many great talents who apparently drank all the time that one wonders whether or not it is entirely coincidental. Is it possible that alcohol can actually unleash one’s creative potential? It is a thesis I have willing to test. Especially since my wife gave me the generous gift last Christmas of a very dear Irish whiskey called Writer’s Tears. Can there be a better name for a bottle of spirits? Unfortunately, it was pricey enough that I have been hesitant to drink very much of it. Perhaps at some moment when I am truly in need of inspiration?

It turns out that someone has actually conducted a study into this. Believe it or not, the Harvard Business Review recently published an article with the definitive headline “Drunk People Are Better at Creative Problem Solving.” There you are. Case closed.

The online version of the article by Alison Beard sums it up in the very first paragraph: “Professor Andrew Jarosz of Mississippi State University and colleagues served vodka-cranberry cocktails to 20 male subjects until their blood alcohol levels neared legal intoxication and then gave each a series of word association problems to solve. Not only did those who imbibed give more correct answers than a sober control group performing the same task, but they also arrived at solutions more quickly. The conclusion: drunk people are better at creative problem solving.”

This immediately raises two questions: 1) was this some sort of April Fool joke, and 2) where can you sign up to take part in a study like this? Professor Jarosz elaborates: “You often hear of great writers, artists, and composers who claim that alcohol enhanced their creativity, or people who say their ideas are better after a few drinks. We wanted to see if we could find evidence to back that up, and though this was a small experiment, we did.” Asked if this means all people in creative jobs should be drinking more, he replies, “Very few professions require you to be 100% thinking outside the box or 100% focused, so I think it’s going to depend on the task you’re doing. You know the old saying ‘Write drunk, edit sober’? Well, there’s a reason the ‘edit’ part is in there.”

There’s the rub. I do not doubt that a certain amount of inebriation can have a positive effect on the creative process for the same reason it can make people feel more relaxed and confident in a potentially stressful situation. Alcohol lowers inhibitions and that can be very liberating emotionally and mentally. I suppose it helps bring out thoughts and ideas that are partially suppressed. Experience, however, suggests that drinking is a disaster when it comes to doing anything that requires concentration, consistency or a quick reaction time. Things that sound brilliant when you are a bit tipsy can be excruciatingly embarrassing when replayed to a sober audience. If you think finding and correcting mistakes—let alone avoiding them in the first place—is difficult under normal circumstances, well, it becomes pretty much impossible if you have been partying in your office.

Professor Jarosz, who describes himself as a craft beer fan, also reports coming across research showing that, surprisingly, people who have been drinking speak with more fluency in a foreign language. I can personally vouch for that, although I have never been sure if a bit of pisco or tequila only makes me think I can speak Spanish better.

In the end, this study strikes me as so many academic reports I read about. After all the research and study, the conclusions always seem to me to have been obvious from the outset. Case in point: “One paper, ‘Lost in the Sauce,’ by Michael Sayette at the University of Pittsburgh and coauthors, reported that people under the influence are more susceptible to mind wandering, which could be helpful in some scenarios but harmful in others.”

Monday, April 23, 2018

The Write Stuff

A reader has been very kind to seek me out about writing advice. Specifically, he asked how I center myself and clear my thoughts prior to writing.

I am flattered because, like him and lots of others, I too am always looking for good advice about writing. I have been amazed to find out how much advice—much of it really good—is out there, probably mainly because so many authors—and also editors and readers—write blogs. While I have happily discussed my own writing process on these pages, I have not tried to pass myself off as any kind of writing expert. After 23 years as a blogger and three novels, I still feel like a beginner who has barely begun to learn to write. Still, I am willing to share my thoughts, for what they are worth.

There are probably as many variations of the writing process as there are writers—if not actually more. I can certainly tell you what works for me, but that does not mean it will be the best way for you or anybody else. For one thing, I do not have the common problem that some aspiring—or even some successful—writers have, which is to regularly find oneself frozen in front of a blank word processor page. So I am probably not the best person to tell you how to beat writer’s block. For that, I still think the best approach is that of novelist Richard Bausch: “When you’re stuck, lower your standards and keep going.”

For what it is worth, here in a nutshell is how I myself approach the challenge of writing a novel. (It occurs to me that I am mostly repeating what lots of other writers have already said.)

Have a clear story in mind. That may be stating the obvious, but there is no point sitting down at a keyboard if you do not know the story you want to tell. I do not plot my books out in excruciating detail before I start—and I sometimes find things happening in the story I did not entirely expect—but I always have a definite story arc in my head and in my notes. That includes a firm sense of where the story begins and where it ends. And that leads to the second thing.

First, write a really good first sentence. Then write a really good last sentence. It is important to have a really good first sentence, so I will spend a lot of time on that—even if it may not seem like it. Then I try to come up with a really good last sentence. Realistically, it is difficult to come up with the last sentence at the very beginning, but it is important to have at the outset an general idea of what that sentence will be like. Usually, about two-thirds through the writing, I come up with a pretty definitive version of the whole final paragraph. That may not work for everyone, but it is essential for me.

Commit to writing a significant number of pages every day. This advice is pretty common. The suggested number of pages varies, but it is important that your goal is set in number of pages as opposed to, say, number of hours per day. I think the reason for that is self-evident. Since I am pretty motivated and disciplined by nature, I have always given myself permission to write the most pages I reasonably can each day—whatever that number might be. And, since I have the luxury of setting my own deadlines, I do not beat myself up about skipping writing days. If, however, you are trying live off your writing, then you would be well advised to put strict benchmarks on yourself.

Lower your standards and keep going. (Yes, I am plagiarizing that from Mr. Bausch.) Some days I feel absolutely inspired and every keystroke I make seems absolutely inspired. (The next day, though, it usually looks like it was typed by random monkeys.) Some days every word I muster feels stale and tired, and I question why I ever bothered to go to school—instead of just staying illiterate. If I make the mistake of reading actual really good writers (for me that’s people like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, but there are many, many others) and comparing their work to mine, well, then I just want to break all my fingers. The trick is to just keep writing—no matter how short from your ideal you are falling—with the thought in your mind that you can always go back and polish it later. Of course, it is better to write something good in the first place, but the fact is that, as the person doing the writing, you will not really be in a position to judge the quality of your own writing until you read it later anyway. Even then, you really are not the best judge. That is what editors are for, but the goal is always not to embarrass yourself in front of the editor.

Make your initial goal to simply finish the first fifty pages. I have read in several places that there is something magic about hitting the fifty-page mark. In my experience, this is actually true. Those first fifty pages are always a lot of work, but at or about that point something strange does happen. Every word is still as much work as it ever was, but overall there seems to be less wind resistance or less friction on the runway. It becomes less easy to stop writing because the story has something akin to momentum or maybe inertia. Let that thought encourage you to keep going.

Accept that you are only about halfway done when you get to the end. As much work as writing can be, it is much more fun writing the first draft of a story than it is to go back and polish and re-write the whole thing. I am sure there are actually writers who enjoy that part of it, but for most of us, I suspect it takes a pretty healthy ego to spend day after day dealing with what is basically ample evidence of your own imperfections. If you want a book you can be proud of, then you just have to suck it up and get on with it. You have to keep reminding yourself that making the writing better is as creative in its own way (though different) as dreaming up the characters and the plot developments.

I am flattered because, like him and lots of others, I too am always looking for good advice about writing. I have been amazed to find out how much advice—much of it really good—is out there, probably mainly because so many authors—and also editors and readers—write blogs. While I have happily discussed my own writing process on these pages, I have not tried to pass myself off as any kind of writing expert. After 23 years as a blogger and three novels, I still feel like a beginner who has barely begun to learn to write. Still, I am willing to share my thoughts, for what they are worth.

There are probably as many variations of the writing process as there are writers—if not actually more. I can certainly tell you what works for me, but that does not mean it will be the best way for you or anybody else. For one thing, I do not have the common problem that some aspiring—or even some successful—writers have, which is to regularly find oneself frozen in front of a blank word processor page. So I am probably not the best person to tell you how to beat writer’s block. For that, I still think the best approach is that of novelist Richard Bausch: “When you’re stuck, lower your standards and keep going.”

For what it is worth, here in a nutshell is how I myself approach the challenge of writing a novel. (It occurs to me that I am mostly repeating what lots of other writers have already said.)

Have a clear story in mind. That may be stating the obvious, but there is no point sitting down at a keyboard if you do not know the story you want to tell. I do not plot my books out in excruciating detail before I start—and I sometimes find things happening in the story I did not entirely expect—but I always have a definite story arc in my head and in my notes. That includes a firm sense of where the story begins and where it ends. And that leads to the second thing.

First, write a really good first sentence. Then write a really good last sentence. It is important to have a really good first sentence, so I will spend a lot of time on that—even if it may not seem like it. Then I try to come up with a really good last sentence. Realistically, it is difficult to come up with the last sentence at the very beginning, but it is important to have at the outset an general idea of what that sentence will be like. Usually, about two-thirds through the writing, I come up with a pretty definitive version of the whole final paragraph. That may not work for everyone, but it is essential for me.

Commit to writing a significant number of pages every day. This advice is pretty common. The suggested number of pages varies, but it is important that your goal is set in number of pages as opposed to, say, number of hours per day. I think the reason for that is self-evident. Since I am pretty motivated and disciplined by nature, I have always given myself permission to write the most pages I reasonably can each day—whatever that number might be. And, since I have the luxury of setting my own deadlines, I do not beat myself up about skipping writing days. If, however, you are trying live off your writing, then you would be well advised to put strict benchmarks on yourself.

Lower your standards and keep going. (Yes, I am plagiarizing that from Mr. Bausch.) Some days I feel absolutely inspired and every keystroke I make seems absolutely inspired. (The next day, though, it usually looks like it was typed by random monkeys.) Some days every word I muster feels stale and tired, and I question why I ever bothered to go to school—instead of just staying illiterate. If I make the mistake of reading actual really good writers (for me that’s people like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, but there are many, many others) and comparing their work to mine, well, then I just want to break all my fingers. The trick is to just keep writing—no matter how short from your ideal you are falling—with the thought in your mind that you can always go back and polish it later. Of course, it is better to write something good in the first place, but the fact is that, as the person doing the writing, you will not really be in a position to judge the quality of your own writing until you read it later anyway. Even then, you really are not the best judge. That is what editors are for, but the goal is always not to embarrass yourself in front of the editor.

Make your initial goal to simply finish the first fifty pages. I have read in several places that there is something magic about hitting the fifty-page mark. In my experience, this is actually true. Those first fifty pages are always a lot of work, but at or about that point something strange does happen. Every word is still as much work as it ever was, but overall there seems to be less wind resistance or less friction on the runway. It becomes less easy to stop writing because the story has something akin to momentum or maybe inertia. Let that thought encourage you to keep going.

Accept that you are only about halfway done when you get to the end. As much work as writing can be, it is much more fun writing the first draft of a story than it is to go back and polish and re-write the whole thing. I am sure there are actually writers who enjoy that part of it, but for most of us, I suspect it takes a pretty healthy ego to spend day after day dealing with what is basically ample evidence of your own imperfections. If you want a book you can be proud of, then you just have to suck it up and get on with it. You have to keep reminding yourself that making the writing better is as creative in its own way (though different) as dreaming up the characters and the plot developments.

Friday, April 13, 2018

Fitness of Character

How do writers come up with their characters?

The suspicion with novelists—especially first-time ones—is that their protagonists are thinly-veiled versions of themselves. Writers known mainly for one main character—Ian Fleming comes to mind—are frequently seen to have deliberately made that character their alter ego.

But what about the other characters, besides the main one, who populate a novel? Where do they come from?

I suppose in the worst of cases they spring from whatever mechanical need there is to advance the plot. Or perhaps they are just slightly modified stock characters from any number of examples of stock fiction. What writers and readers would prefer, of course, is that every character in a story—even the most minor—would spring to life as a fully realized creation that lives and breathes naturally and is unique in the same way that every human being is non-identical to all other human beings.

My own experience is that a character may begin as being somewhat “like” someone I have known in my life, but by the time she has become fully immersed in the biosphere of the story, she has taken on her own life and overshadowed the original inspiration. It is amazing how your characters—not unlike your children—may begin by depending on you entirely but, before you know it, they have minds and wills of their own. As a writer, you may end up feeling less like an author than a stenographer.

No one has really queried me about where the various characters in Lautaro’s Spear came from—aside from the inevitable accusations that Dallas Green is really me. (For the millionth time, he’s not.) As for the other characters, individual readers have had their favorites and their non-favorites, but most (of the ones who have communicated with me anyway) have liked Marty, the somewhat mysterious proprietor of a hole-in-the-wall Mexican eatery hidden away in San Francisco’s Mission District. Interestingly, he is the one character in the book whom I more or less appropriated full-cloth from real life. It so happens that back in the 1980s when I was working in the Lower Queen Anne area of Seattle, I had my own Marty.

He was pretty much as described, although he did not have a sidekick Leonides (that I was aware of anyway) and I was never invited to his home. And he never made me a margarita, although I am sure it would have been good. He was just a guy who served up Mexican food and liked to talk. Always anxious for an opportunity to practice my Spanish, just like Dallas I would converse with him en español, which he clearly understood, but he would insist on responding in English. And just as in the book, when I mentioned my year in Chile during the Pinochet regime, he began dropping hints that he somehow had something to do with the coup that overthrew Salvador Allende and brought Pinochet to power. I could never be sure, when he said “yeah, we did on a job on him,” whether he was speaking of the U.S. collectively or some other community he identified with or, most tantalizingly of all possibilities, some elite squad of which he was personally a member. The last idea fascinated me. What if he was some sort of secret agent?

If that had been the case, how likely would it have been for him to have wound up cooking enchiladas in the shadow in of the Space Needle? In hindsight, perhaps more likely than I might have thought. In the late 1980s and early 1990s I was a regular customer of a Mexican restaurant in downtown Redmond. Years later I learned that one of the people cooking the food there had been Henry Hill (using a new identity), an FBI mob informant whose story became the basis for the Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas.

I never actually learned the name of the cook who inspired the character for my book. In Lautaro’s Spear I called him Marty. That was my own little tribute to the character played by Edward James Olmos in the TV series Miami Vice, Lt. Martin Castillo. In all my years of television viewing, that was definitely one of the best cases of an ordinary-seeming secondary character being revealed, bit by bit over time, to be way more interesting than was first apparent. I wonder who he was based on.

The suspicion with novelists—especially first-time ones—is that their protagonists are thinly-veiled versions of themselves. Writers known mainly for one main character—Ian Fleming comes to mind—are frequently seen to have deliberately made that character their alter ego.

But what about the other characters, besides the main one, who populate a novel? Where do they come from?

I suppose in the worst of cases they spring from whatever mechanical need there is to advance the plot. Or perhaps they are just slightly modified stock characters from any number of examples of stock fiction. What writers and readers would prefer, of course, is that every character in a story—even the most minor—would spring to life as a fully realized creation that lives and breathes naturally and is unique in the same way that every human being is non-identical to all other human beings.

My own experience is that a character may begin as being somewhat “like” someone I have known in my life, but by the time she has become fully immersed in the biosphere of the story, she has taken on her own life and overshadowed the original inspiration. It is amazing how your characters—not unlike your children—may begin by depending on you entirely but, before you know it, they have minds and wills of their own. As a writer, you may end up feeling less like an author than a stenographer.

No one has really queried me about where the various characters in Lautaro’s Spear came from—aside from the inevitable accusations that Dallas Green is really me. (For the millionth time, he’s not.) As for the other characters, individual readers have had their favorites and their non-favorites, but most (of the ones who have communicated with me anyway) have liked Marty, the somewhat mysterious proprietor of a hole-in-the-wall Mexican eatery hidden away in San Francisco’s Mission District. Interestingly, he is the one character in the book whom I more or less appropriated full-cloth from real life. It so happens that back in the 1980s when I was working in the Lower Queen Anne area of Seattle, I had my own Marty.

He was pretty much as described, although he did not have a sidekick Leonides (that I was aware of anyway) and I was never invited to his home. And he never made me a margarita, although I am sure it would have been good. He was just a guy who served up Mexican food and liked to talk. Always anxious for an opportunity to practice my Spanish, just like Dallas I would converse with him en español, which he clearly understood, but he would insist on responding in English. And just as in the book, when I mentioned my year in Chile during the Pinochet regime, he began dropping hints that he somehow had something to do with the coup that overthrew Salvador Allende and brought Pinochet to power. I could never be sure, when he said “yeah, we did on a job on him,” whether he was speaking of the U.S. collectively or some other community he identified with or, most tantalizingly of all possibilities, some elite squad of which he was personally a member. The last idea fascinated me. What if he was some sort of secret agent?

If that had been the case, how likely would it have been for him to have wound up cooking enchiladas in the shadow in of the Space Needle? In hindsight, perhaps more likely than I might have thought. In the late 1980s and early 1990s I was a regular customer of a Mexican restaurant in downtown Redmond. Years later I learned that one of the people cooking the food there had been Henry Hill (using a new identity), an FBI mob informant whose story became the basis for the Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas.

I never actually learned the name of the cook who inspired the character for my book. In Lautaro’s Spear I called him Marty. That was my own little tribute to the character played by Edward James Olmos in the TV series Miami Vice, Lt. Martin Castillo. In all my years of television viewing, that was definitely one of the best cases of an ordinary-seeming secondary character being revealed, bit by bit over time, to be way more interesting than was first apparent. I wonder who he was based on.

Tuesday, March 6, 2018

The First Hurdle

The good news that I have now written nine chapters of my next book.

The bad news is that five of them are Chapter 1 and four of them are Chapter 2.

In other words, things are going about normal. With three novels under my belt, I can actually now make sweeping generalizations about my writing process, and here comes one. The early stage involves a lot of writing and re-writing of the initial chapters. More than once I have read that the biggest hurdle to completing a book is getting past the first fifty pages, and I understand why. I do not know if there is something magic about the number fifty, but I do know that it takes about that many pages for the creation of a book to attain lift-off. Until you get to that point, you are like an airplane taxiing on the runway. The main difference, at least in my case, is that the plane is (usually) not continually backing up and starting again from a dead stop. Come to think of it, neither am I, so maybe the airplane comparison is not completely inapt after all.

A lot of things have to happen in those first few chapters that are crucial to everything that happens after. The characters have to be drawn right, which is to say that they must be consistent with what will be happening further down the line. Some characters start out as placeholders or plot devices, and they need to be fleshed out so that the story has some hope of feeling like it is really happening. The writing process takes up too much time for me to want to spend it all with a bunch of robots. Since my characters are going to be residing in my head for months and years, I want them to be good—or at least interesting—company.

Also, events need to happen in a way that leads to where I need the story to go. Plotting a story is basically a long chain of decisions. I suppose the reason that the early stages are more challenging is that there are too many possibilities. Once you get past a certain point, the possibilities become more manageable because so many branches of the decision tree have been pruned.

Maybe a better comparison for explaining the challenge of getting past the first few chapters is lighting a fire. This is an activity that has been particularly relevant lately since it has been extremely cold in Ireland. Since a mass of polar air arrived from Sibera last week (dubbed “the Beast from the East”) and met Storm Emma coming up from the Bay of Biscay, building fires has become a critically important chore so, yes, let us compare the fifty-page barrier to building a fire.

For all the reason mentioned above—and maybe some others—there is something wondrous that happens around fifty pages in. It is akin to the moment when the turf in the fireplace ignites and begins to burn on its own. From that moment on, you are not exactly home free, but everything is easier. You are no longer going back and laboring on top of already-trodden ground. You can focus entirely on going forward. If the first few chapters tend to get over-written, the rest of the book—at least in my case—is always in danger of not being sufficiently polished. Because of the momentum. I just want to keep the story going and not “waste” time looking back.

I am still looking forward to getting to that point, but at least I know from experience it is not far away.

In the meantime, let us observe that today would have been the 91st birthday of the journalist and novelist Gabriel García Márquez. He was born on March 6, 1927, in Aracataca, Colombia, which he immortalized in his books as the fictionalized village of Macondo. I have previously written on one of my other blogs about what his works—first and foremost One Hundred Years of Solitude—meant to me, particularly at the point in my life when I first read and studied them in South America.

Literary heroes can be daunting because they pose the danger of making someone like me feel his attempts at writing are pointless when there are books of García Márquez’s caliber already out there. Personally, I prefer instead to take comfort from the probable fact that, with each and every one of his books, he would have experienced the same exact frustration as me in getting past those first fifty pages.

The bad news is that five of them are Chapter 1 and four of them are Chapter 2.

In other words, things are going about normal. With three novels under my belt, I can actually now make sweeping generalizations about my writing process, and here comes one. The early stage involves a lot of writing and re-writing of the initial chapters. More than once I have read that the biggest hurdle to completing a book is getting past the first fifty pages, and I understand why. I do not know if there is something magic about the number fifty, but I do know that it takes about that many pages for the creation of a book to attain lift-off. Until you get to that point, you are like an airplane taxiing on the runway. The main difference, at least in my case, is that the plane is (usually) not continually backing up and starting again from a dead stop. Come to think of it, neither am I, so maybe the airplane comparison is not completely inapt after all.

A lot of things have to happen in those first few chapters that are crucial to everything that happens after. The characters have to be drawn right, which is to say that they must be consistent with what will be happening further down the line. Some characters start out as placeholders or plot devices, and they need to be fleshed out so that the story has some hope of feeling like it is really happening. The writing process takes up too much time for me to want to spend it all with a bunch of robots. Since my characters are going to be residing in my head for months and years, I want them to be good—or at least interesting—company.

Also, events need to happen in a way that leads to where I need the story to go. Plotting a story is basically a long chain of decisions. I suppose the reason that the early stages are more challenging is that there are too many possibilities. Once you get past a certain point, the possibilities become more manageable because so many branches of the decision tree have been pruned.

Maybe a better comparison for explaining the challenge of getting past the first few chapters is lighting a fire. This is an activity that has been particularly relevant lately since it has been extremely cold in Ireland. Since a mass of polar air arrived from Sibera last week (dubbed “the Beast from the East”) and met Storm Emma coming up from the Bay of Biscay, building fires has become a critically important chore so, yes, let us compare the fifty-page barrier to building a fire.

For all the reason mentioned above—and maybe some others—there is something wondrous that happens around fifty pages in. It is akin to the moment when the turf in the fireplace ignites and begins to burn on its own. From that moment on, you are not exactly home free, but everything is easier. You are no longer going back and laboring on top of already-trodden ground. You can focus entirely on going forward. If the first few chapters tend to get over-written, the rest of the book—at least in my case—is always in danger of not being sufficiently polished. Because of the momentum. I just want to keep the story going and not “waste” time looking back.

I am still looking forward to getting to that point, but at least I know from experience it is not far away.

In the meantime, let us observe that today would have been the 91st birthday of the journalist and novelist Gabriel García Márquez. He was born on March 6, 1927, in Aracataca, Colombia, which he immortalized in his books as the fictionalized village of Macondo. I have previously written on one of my other blogs about what his works—first and foremost One Hundred Years of Solitude—meant to me, particularly at the point in my life when I first read and studied them in South America.

Literary heroes can be daunting because they pose the danger of making someone like me feel his attempts at writing are pointless when there are books of García Márquez’s caliber already out there. Personally, I prefer instead to take comfort from the probable fact that, with each and every one of his books, he would have experienced the same exact frustration as me in getting past those first fifty pages.

Thursday, February 1, 2018

Art of the Sequel

In my previous post I explained in a fair amount of detail how my first novel Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead came about. There is no need, though, to explain how Lautaro’s Spear came about, right? It’s just a continuation of the first book because it is a sequel or, as I explained in another previous post, just another book in the same “novel sequence.”

Okay, let’s be real. Lautaro’s Spear is a sequel. So how does it measure up to the definition of sequels that I have oft cited on my movie web site? As I keep saying, a sequel is basically the same story as the original movie or book but re-worked to give the impression that it is actually a new story that advances some overall storyline. Also, the conventions of the sequel require that, when the original story is retold, everything must be bigger and better.

So how does Lautaro’s Spear measure up as a sequel? Well, you can certainly make the argument that it is the same story. Once again Dallas feels his life in California closing in on him and decides to escape by taking off for foreign parts. During his foreign adventure he meets and falls in love with a woman and he forms a strong bond with a new Hispanic friend. Also, he gets mixed up with a bit of political intrigue that leads him to a dicey border crossing.

Had you spotted all those parallels? Actually, come to think of it, if all those coincidences constitute a sequel, then doesn’t The Three Towers of Afranor—if you substitute Alinvayl for California and Afranorian for Hispanic—technically qualify as a sequel too? Actually, when it comes down to it, isn’t every story basically about a journey of some sort?

Okay, I got a bit silly there, but there is a fair amount of truth in what I was saying about sequels. Consumers of fiction, I believe, read or view sequels precisely because they enjoyed the original work and want to have that experience again. Of course, the author cannot give them the exact same experience again because you can only experience—really experience—a particular thing once. If you experience it again, then you are re-experiencing it, which is something different but still valid in its own right. After all, in the sequel experience there is something pleasing about subtle reminders of the original experience, the recognition that, yes, we have been here before, although things were different then.

The real challenge comes with the sequel to a sequel—something some people call a “threequel.” Just doing the same thing but bigger still and better still does not quite cut it. That is why so many third installments in a series (cf. Superman III, Godfather III) fall flat. To avoid this, writers sometimes go in a different direction. They go about de-constructing the original story instead of just retelling it. That appeals to some readers/viewers, but others are put off by the fact that the writer no longer seems to take the story and characters seriously.

Fortunately, I still have a bit of time—and a whole other book to get through—before I have to decide exactly how to make Dallas’s sequel’s sequel work. I can promise you it will be something totally original—but just the same.

Okay, let’s be real. Lautaro’s Spear is a sequel. So how does it measure up to the definition of sequels that I have oft cited on my movie web site? As I keep saying, a sequel is basically the same story as the original movie or book but re-worked to give the impression that it is actually a new story that advances some overall storyline. Also, the conventions of the sequel require that, when the original story is retold, everything must be bigger and better.

So how does Lautaro’s Spear measure up as a sequel? Well, you can certainly make the argument that it is the same story. Once again Dallas feels his life in California closing in on him and decides to escape by taking off for foreign parts. During his foreign adventure he meets and falls in love with a woman and he forms a strong bond with a new Hispanic friend. Also, he gets mixed up with a bit of political intrigue that leads him to a dicey border crossing.

Had you spotted all those parallels? Actually, come to think of it, if all those coincidences constitute a sequel, then doesn’t The Three Towers of Afranor—if you substitute Alinvayl for California and Afranorian for Hispanic—technically qualify as a sequel too? Actually, when it comes down to it, isn’t every story basically about a journey of some sort?

Okay, I got a bit silly there, but there is a fair amount of truth in what I was saying about sequels. Consumers of fiction, I believe, read or view sequels precisely because they enjoyed the original work and want to have that experience again. Of course, the author cannot give them the exact same experience again because you can only experience—really experience—a particular thing once. If you experience it again, then you are re-experiencing it, which is something different but still valid in its own right. After all, in the sequel experience there is something pleasing about subtle reminders of the original experience, the recognition that, yes, we have been here before, although things were different then.

The real challenge comes with the sequel to a sequel—something some people call a “threequel.” Just doing the same thing but bigger still and better still does not quite cut it. That is why so many third installments in a series (cf. Superman III, Godfather III) fall flat. To avoid this, writers sometimes go in a different direction. They go about de-constructing the original story instead of just retelling it. That appeals to some readers/viewers, but others are put off by the fact that the writer no longer seems to take the story and characters seriously.

Fortunately, I still have a bit of time—and a whole other book to get through—before I have to decide exactly how to make Dallas’s sequel’s sequel work. I can promise you it will be something totally original—but just the same.

Wednesday, January 10, 2018

Percolation

So I survived another winter solstice, another Christmas, another New Year. The dark end of the annual journey around the sun is past, and things are returning to as normal as they get in my house. It is actually possible to think about writing fiction again.

During holiday periods, when schools and businesses are closed and the world is oppressively gloomy outside, I enjoy my lie-ins. They are strangely fertile moments creatively. In the early-morning dark, my brain finds itself entering dream states where my mind plays out various vignettes, while slipping in and out of wakefulness. Normally, these would be scenes from the next book but, against my will, my brain keeps wanting to skip ahead to the third book about Dallas Green. Interesting things lie in store for him.

Dallas has become a near-constant companion for me, which is kind of strange. He really has taken on a life of his own in my head. This must be what it is like to be possessed by a ghost.

The thing is, I never actually meant to write a book about someone like Dallas. The seeds for Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead go all the way back to the year I lived in Chile during the fourth year of the Pinochet dictatorship. Inspired by such writers as Colombia’s Gabriel García Márquez and Guatemala’s Miguel Ángel Asturias, I wanted to create a literary work around the rise and fall of an idealistic but flawed Latin American leader. It would be a thinly veiled allegory, mirroring the revolutionary rise and inevitable crucification of Jesus. Daunted by the risks of inauthenticity and cultural appropriation, I decided the saga would necessarily be related by a foreigner. He would be an idealistic young North American. As an outsider, he would be imbued with a fair amount of skepticism of this political movement in the name of the people. In other words, if my Salvador Allende figure was to be Christ, then my North American would be his most doubtful disciple, Thomas. Thus the point-of-view character’s name would morph from doubting Thomas to Tommy Dowd.

The epic percolated in my mind for many years, but one thing or another—like the better part of decade disappearing like a flash of light into the time-warping wormhole of the software industry—kept me from writing more than a few chapters. Finally, marriage and relocation to the Emerald Isle gave my mind space to return to the long-neglected story. By then, though, a funny thing had happened to the tale. The story I had mapped out was just not working for me. Somewhere along the way, I got an idea. What if I did not tell the story directly? What if the story was lurking in the background of someone else’s story? Inspired by my own childhood exploits with my often-feckless best friend, I conceived an early-1970s odyssey adventure à la Huckleberry Finn. Tommy Dowd would not actually appear in the story. He would be the McGuffin, the reason for the pair’s adventure. After his disappearance, they would head south to look for him. They would go outside of their own country, their own culture, their own language and their own comfort zone. They would be changed forever. And all the time—just outside of their peripheral vision—would be the story of Tommy and that idealistic leader who led himself and his followers to doom.

It was meant to a self-contained story, a one-off. It never occurred to me to go beyond the end of Dallas and Lonnie’s adventure in 1971. Other people, however, told me that I had to continue the story. Some made suggestions for what would happen next. It was a strange feeling. Dallas was no longer just an idea in my head. He was now out in the world. He no longer belonged to me alone. The more I thought about this, the more I realized that I too wanted to know what else happened to him.

Now that I have taken him nine years further through the twentieth century, I want to see his story through at least another few years.

Before I do that, however, I have another story that has been percolating for a very long time. One about ghosts and spirits and curses and demons and ancient evil and stormy weather. It wants its chance to see the light of day too. Fair’s fair. It has waited long enough. It is now at the head of the queue.

During holiday periods, when schools and businesses are closed and the world is oppressively gloomy outside, I enjoy my lie-ins. They are strangely fertile moments creatively. In the early-morning dark, my brain finds itself entering dream states where my mind plays out various vignettes, while slipping in and out of wakefulness. Normally, these would be scenes from the next book but, against my will, my brain keeps wanting to skip ahead to the third book about Dallas Green. Interesting things lie in store for him.

Dallas has become a near-constant companion for me, which is kind of strange. He really has taken on a life of his own in my head. This must be what it is like to be possessed by a ghost.

The thing is, I never actually meant to write a book about someone like Dallas. The seeds for Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead go all the way back to the year I lived in Chile during the fourth year of the Pinochet dictatorship. Inspired by such writers as Colombia’s Gabriel García Márquez and Guatemala’s Miguel Ángel Asturias, I wanted to create a literary work around the rise and fall of an idealistic but flawed Latin American leader. It would be a thinly veiled allegory, mirroring the revolutionary rise and inevitable crucification of Jesus. Daunted by the risks of inauthenticity and cultural appropriation, I decided the saga would necessarily be related by a foreigner. He would be an idealistic young North American. As an outsider, he would be imbued with a fair amount of skepticism of this political movement in the name of the people. In other words, if my Salvador Allende figure was to be Christ, then my North American would be his most doubtful disciple, Thomas. Thus the point-of-view character’s name would morph from doubting Thomas to Tommy Dowd.

The epic percolated in my mind for many years, but one thing or another—like the better part of decade disappearing like a flash of light into the time-warping wormhole of the software industry—kept me from writing more than a few chapters. Finally, marriage and relocation to the Emerald Isle gave my mind space to return to the long-neglected story. By then, though, a funny thing had happened to the tale. The story I had mapped out was just not working for me. Somewhere along the way, I got an idea. What if I did not tell the story directly? What if the story was lurking in the background of someone else’s story? Inspired by my own childhood exploits with my often-feckless best friend, I conceived an early-1970s odyssey adventure à la Huckleberry Finn. Tommy Dowd would not actually appear in the story. He would be the McGuffin, the reason for the pair’s adventure. After his disappearance, they would head south to look for him. They would go outside of their own country, their own culture, their own language and their own comfort zone. They would be changed forever. And all the time—just outside of their peripheral vision—would be the story of Tommy and that idealistic leader who led himself and his followers to doom.

It was meant to a self-contained story, a one-off. It never occurred to me to go beyond the end of Dallas and Lonnie’s adventure in 1971. Other people, however, told me that I had to continue the story. Some made suggestions for what would happen next. It was a strange feeling. Dallas was no longer just an idea in my head. He was now out in the world. He no longer belonged to me alone. The more I thought about this, the more I realized that I too wanted to know what else happened to him.

Now that I have taken him nine years further through the twentieth century, I want to see his story through at least another few years.

Before I do that, however, I have another story that has been percolating for a very long time. One about ghosts and spirits and curses and demons and ancient evil and stormy weather. It wants its chance to see the light of day too. Fair’s fair. It has waited long enough. It is now at the head of the queue.

Wednesday, December 20, 2017

Reindeer Games

By far the cheapest entertainment available on the internet is your search engine. There are endless hours of enjoyment to be had simply by entering your name in the search field and then poring over the pages of results.

This is not something I normally spend a lot of time on, but I do periodically search for the titles of my three books, just to see if they are being mentioned anywhere, what sites are offering them for sale and—mostly, it often seems—to see how many bogus web sites are offering to let you download them for free. (Note: a surprising number of sites offer the books in various formats, but—spoiler alert—so far none I have found really have a digital or audio version of the book available.)

Often, though, I come across amusing and interesting random mentions of my books. Here is one I found the other day.

This is a legitimate-looking site called Parenting.com and, in their online shop, they seem to be offering my first novel Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead for sale—but not quite. They have it listed in the category “Toys & Activities” and sub-category “Childrens [sic] Books.” For the record, in case there is any confusion, Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead is definitely not a children’s book. Please do not let a child anywhere near it. Fortunately, no unsuspecting parents are in any apparent risk of inadvertently buying it from the Parenting.com web site for their tot since there is a red label across the cover that says “Not Available.” Whew.

Interestingly, the site has altered the title to make it even longer by adding the word “Green” for no clearly obvious reason. Kind of takes me back to the 1960s when the Swedish movie I Am Curious (Yellow) had a fair bit of notoriety in America, but I digress.

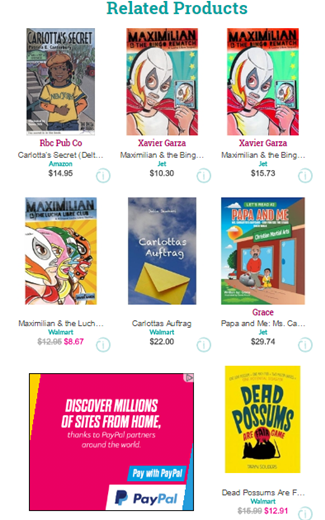

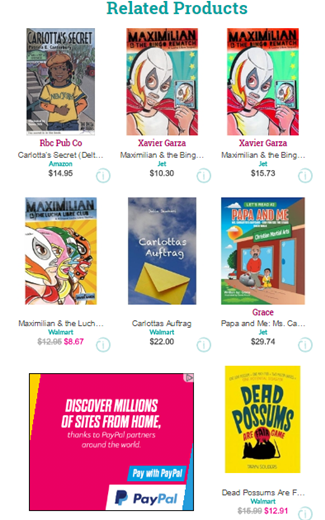

As is often the case, the most entertaining part of the page is the section further down labeled “Related Products.” Once again, these are mainly books in which random words from the title have been matched up, so we get titles like Carlotta’s Secret and Maximilian & the Bingo Rematch. Less obviously, we also get Papa & Me. At least these seem to be actual children’s books.

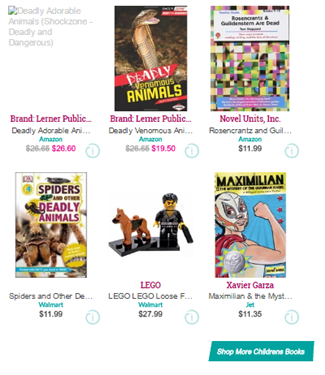

If we continue down the list, we find some less obvious matches. Okay, Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead is one we have come across before, but what’s the deal with Deadly Venomous Animals and Spiders and Other Deadly Animals? The most amusing, though, is the black-clad Lego figure.

On closer inspection, we see why he was included. He is described as “LEGO LEGO Loose Furious Maximilian Minifigure.” In the brackets following his name, we learn why Maximilian is so furious. He is an Apocalypse Survivor.

As I say, by far the cheapest entertainment available on the internet.

Speaking of shopping web sites, Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead, The Three Towers of Afranor and Lautaro’s Spear are all still available from the various online sellers, as indicated on the right-hand side of this page. (But not Parenting.com)

Happy Christmas!

This is not something I normally spend a lot of time on, but I do periodically search for the titles of my three books, just to see if they are being mentioned anywhere, what sites are offering them for sale and—mostly, it often seems—to see how many bogus web sites are offering to let you download them for free. (Note: a surprising number of sites offer the books in various formats, but—spoiler alert—so far none I have found really have a digital or audio version of the book available.)

Often, though, I come across amusing and interesting random mentions of my books. Here is one I found the other day.

This is a legitimate-looking site called Parenting.com and, in their online shop, they seem to be offering my first novel Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead for sale—but not quite. They have it listed in the category “Toys & Activities” and sub-category “Childrens [sic] Books.” For the record, in case there is any confusion, Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead is definitely not a children’s book. Please do not let a child anywhere near it. Fortunately, no unsuspecting parents are in any apparent risk of inadvertently buying it from the Parenting.com web site for their tot since there is a red label across the cover that says “Not Available.” Whew.

Interestingly, the site has altered the title to make it even longer by adding the word “Green” for no clearly obvious reason. Kind of takes me back to the 1960s when the Swedish movie I Am Curious (Yellow) had a fair bit of notoriety in America, but I digress.

As is often the case, the most entertaining part of the page is the section further down labeled “Related Products.” Once again, these are mainly books in which random words from the title have been matched up, so we get titles like Carlotta’s Secret and Maximilian & the Bingo Rematch. Less obviously, we also get Papa & Me. At least these seem to be actual children’s books.

If we continue down the list, we find some less obvious matches. Okay, Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead is one we have come across before, but what’s the deal with Deadly Venomous Animals and Spiders and Other Deadly Animals? The most amusing, though, is the black-clad Lego figure.

On closer inspection, we see why he was included. He is described as “LEGO LEGO Loose Furious Maximilian Minifigure.” In the brackets following his name, we learn why Maximilian is so furious. He is an Apocalypse Survivor.

As I say, by far the cheapest entertainment available on the internet.

Speaking of shopping web sites, Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead, The Three Towers of Afranor and Lautaro’s Spear are all still available from the various online sellers, as indicated on the right-hand side of this page. (But not Parenting.com)

Happy Christmas!

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Happy Birthday Again, Dallas

Has it been a whole year already? Yes, it has. It was one year ago today that I revealed to the world at large that December 7 is—in addition to being the anniversary of the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack—the birthday of the protagonist of two of my novels.

It would be more than nine months after that, however, before readers would get a chance to learn for themselves how and why Dallas Green’s birth date figured into the plot of Lautaro’s Spear. In the book’s final chapter, it turned out that he celebrated—if that’s the word for it—his birthday alone as the culmination of a rather interesting and ultimately difficult year. And there was one last surprise awaiting him that night. I wonder if his birthday this year, 37 years later, is equally interesting for him.

That’s the funny thing about fictional characters that you create yourself. You get to decide what happens to them—up to a point. Last year, when I teased the story to be recounted in Lauraro’s Spear, it was all subject to change. In fact, the first draft was only half-complete at that point. I could make Dallas do anything I wanted him to do—subject, of course, to my desire to keep his character consistent—and I could make anything happen to him that I wanted. That’s quite a bit of power. His life between 1971 and 1980 was completely in my hands. Now though, the book has been published and the events in Lautaro’s Spear are canon. Short of a trick à la Dallas (the old TV series, not my character) like saying the whole book was a dream, I cannot change what has happened to young Mr. Green. It is part of history.

On the other hand, his life from December 1980 onwards is all mine to play with. Every morning I wake up with my barely conscious mind playing out new scenarios for the ensuing years, leading up to probably 1993. I have learned to savor this part of the writing process. No more than one’s own personal life, there is something grand about having every possibility still ahead of you.

This process of weighing and pondering and inventing will go on for some time. As before, I think it is good and necessary to put a healthy gap before the next installment of Dallas’s life by writing something completely different in between. That something will be the supernatural adventure I have wanted to write ever since, well, all those afternoons I ran home from school with the aim of being in front of the television in time to catch the latest episode of Dark Shadows. Is it too soon to start teasing it already? Well, I can tell you that it involves a very old house on a mysterious island in Puget Sound. I have been looking around for old houses that I could use as inspiration and perhaps even an eventual book cover. Fortunately, there is no shortage of such structures in the west of Ireland.

I lately came across this photo that my wife took when we were visiting the town of Donegal earlier this year. What do you think? It definitely has the right vibe, although it is technically a castle rather than a house—and it does not look like it is on a small craggy island in the sea. It is certainly a start, though. I have already done much of the work on another important part of the writing process: creating a spooky music playlist on Spotify for all those hours of staring at the keyboard.

This is probably a good time to mention that Lautaro’s Spear is, of course, still on sale—as are Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead and The Three Towers of Afranor—in paperback and various digital formats, and the links for ordering all of them are somewhere on this page off to the right-hand side. Also, Christmas will be here soon. You probably have people on your shopping list, who like to read and who may not have read any or all of these books. Work out for yourself the best thing to do.

It would be more than nine months after that, however, before readers would get a chance to learn for themselves how and why Dallas Green’s birth date figured into the plot of Lautaro’s Spear. In the book’s final chapter, it turned out that he celebrated—if that’s the word for it—his birthday alone as the culmination of a rather interesting and ultimately difficult year. And there was one last surprise awaiting him that night. I wonder if his birthday this year, 37 years later, is equally interesting for him.

That’s the funny thing about fictional characters that you create yourself. You get to decide what happens to them—up to a point. Last year, when I teased the story to be recounted in Lauraro’s Spear, it was all subject to change. In fact, the first draft was only half-complete at that point. I could make Dallas do anything I wanted him to do—subject, of course, to my desire to keep his character consistent—and I could make anything happen to him that I wanted. That’s quite a bit of power. His life between 1971 and 1980 was completely in my hands. Now though, the book has been published and the events in Lautaro’s Spear are canon. Short of a trick à la Dallas (the old TV series, not my character) like saying the whole book was a dream, I cannot change what has happened to young Mr. Green. It is part of history.

On the other hand, his life from December 1980 onwards is all mine to play with. Every morning I wake up with my barely conscious mind playing out new scenarios for the ensuing years, leading up to probably 1993. I have learned to savor this part of the writing process. No more than one’s own personal life, there is something grand about having every possibility still ahead of you.

This process of weighing and pondering and inventing will go on for some time. As before, I think it is good and necessary to put a healthy gap before the next installment of Dallas’s life by writing something completely different in between. That something will be the supernatural adventure I have wanted to write ever since, well, all those afternoons I ran home from school with the aim of being in front of the television in time to catch the latest episode of Dark Shadows. Is it too soon to start teasing it already? Well, I can tell you that it involves a very old house on a mysterious island in Puget Sound. I have been looking around for old houses that I could use as inspiration and perhaps even an eventual book cover. Fortunately, there is no shortage of such structures in the west of Ireland.

I lately came across this photo that my wife took when we were visiting the town of Donegal earlier this year. What do you think? It definitely has the right vibe, although it is technically a castle rather than a house—and it does not look like it is on a small craggy island in the sea. It is certainly a start, though. I have already done much of the work on another important part of the writing process: creating a spooky music playlist on Spotify for all those hours of staring at the keyboard.

This is probably a good time to mention that Lautaro’s Spear is, of course, still on sale—as are Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead and The Three Towers of Afranor—in paperback and various digital formats, and the links for ordering all of them are somewhere on this page off to the right-hand side. Also, Christmas will be here soon. You probably have people on your shopping list, who like to read and who may not have read any or all of these books. Work out for yourself the best thing to do.

Thursday, November 16, 2017

Other Bildungsromans Are Available

Okay, so maybe my novel about young male friendship (or its sequel) has not yet been made into a movie, but I know that there is an audience for such films. I know this because such movies keep getting made. And I know that such movies keep getting made because, once I finished writing Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead, I found myself compulsively reading other authors’ books about intense youthful male friendships. One of those film adaptations has recently been released to critical acclaim, and another has been making the rounds of various international film festivals.

Egypt-born American author André Aciman’s 2007 novel Call Me by Your Name is not really so much about friendship as infatuation. Aciman does a skillful job of capturing the excitement and frustration of being a precocious teenager in a privileged, intellectually stimulating environment. The time is summer 1983, and the narrator is 17-year-old American-Italian Jewish boy Elio, living on the beautiful Italian coast. Over the course of the story, he becomes increasingly obsessed with confident and handsome Oliver, his professor father’s 24-year-old live-in summer intern from the States. The book is enjoyable because who would not want to spend his teenage years in such a beautiful place and in such an interesting environment? While the young narrator is (understandably) self-absorbed and sometimes whiny, we cannot help but like him because he has the attractiveness of uncanny intelligence. (He plays the piano and seems to have read absolutely everything.) Not surprisingly, the book and, now, the movie have been embraced enthusiastically by gay audiences, but I was intrigued by an interview with the film’s Sicilian-born director Luca Guadagnino (I Am Love, A Bigger Splash) in which he insisted that he did not view it as a “gay” love story. I understand what he means. While the love scenes are memorably passionate, the book is not steeped in the familiar gay themes of writers like, say, James Baldwin. The genders of the characters are nearly irrelevant to what Aciman’s book is concerned about. The movie version’s screenplay is by the venerable James Ivory, whose many films (made with his late partner Ismail Merchant) included an adaptation of E.M. Forster’s gay-themed Maurice.

If we wish to compare, then Call Me by Your Name is the near-polar opposite of Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead—despite both of them being first-hand accounts by male teenagers in the mid-to-late twentieth century, who are facing into adulthood. Elio does not have to flee his family and home for his journey. Unlike Dallas Green’s, his journey is mostly internal and definitely solitary. Despite his wary-then-passionate relationship with Oliver, he seems to be someone who has grown up without a best friend.

A better comparison to Max & Carly is Australian Tim Winton’s 2008 novel Breath. In fact, the coincidental parallels are are nearly, well, breathtaking. As with my book, it is set in the 1970s and the focus of the story is a strong, nearly desperate, friendship between two boys in the backwater of Australia’s western coast. The dynamic between Bruce Pike, the only son of a modest and conservative couple, and Ivan Loon, the wild son of a feckless father, is much like that of Dallas and Lonnie. In fact, given the nicknames of Winton’s pair, Pikelet and Loonie, I found myself working hard not to read Loonie as Lonnie. What binds the two is their mutual love of surfing and the need to test their courage against bigger and bigger waves. They fall in thrall to Sando, a onetime surfing legend now living in self-imposed obscurity with his taciturn young American wife. For the most part, the book is a really good read, although I found the final chapters a bit of let-down. Pikelet narrates the story from the perspective of middle age, and the rapid encapsulation of his (mostly depressing) later life is an unwelcome turn after the high spirits of the earlier sections. Overall, though, it is a very good evocation of being young and male, having and losing a close friend, falling in love and getting on with the not-always-easy business of adult life.

The film adaptation of Breath is directed by Tasmania-born Simon Baker, who also plays the role of Sando. He is probably best known to U.S. audiences, who may not even realize he is not American, as the star of the long-running detective show The Mentalist.

Egypt-born American author André Aciman’s 2007 novel Call Me by Your Name is not really so much about friendship as infatuation. Aciman does a skillful job of capturing the excitement and frustration of being a precocious teenager in a privileged, intellectually stimulating environment. The time is summer 1983, and the narrator is 17-year-old American-Italian Jewish boy Elio, living on the beautiful Italian coast. Over the course of the story, he becomes increasingly obsessed with confident and handsome Oliver, his professor father’s 24-year-old live-in summer intern from the States. The book is enjoyable because who would not want to spend his teenage years in such a beautiful place and in such an interesting environment? While the young narrator is (understandably) self-absorbed and sometimes whiny, we cannot help but like him because he has the attractiveness of uncanny intelligence. (He plays the piano and seems to have read absolutely everything.) Not surprisingly, the book and, now, the movie have been embraced enthusiastically by gay audiences, but I was intrigued by an interview with the film’s Sicilian-born director Luca Guadagnino (I Am Love, A Bigger Splash) in which he insisted that he did not view it as a “gay” love story. I understand what he means. While the love scenes are memorably passionate, the book is not steeped in the familiar gay themes of writers like, say, James Baldwin. The genders of the characters are nearly irrelevant to what Aciman’s book is concerned about. The movie version’s screenplay is by the venerable James Ivory, whose many films (made with his late partner Ismail Merchant) included an adaptation of E.M. Forster’s gay-themed Maurice.

If we wish to compare, then Call Me by Your Name is the near-polar opposite of Maximilian and Carlotta Are Dead—despite both of them being first-hand accounts by male teenagers in the mid-to-late twentieth century, who are facing into adulthood. Elio does not have to flee his family and home for his journey. Unlike Dallas Green’s, his journey is mostly internal and definitely solitary. Despite his wary-then-passionate relationship with Oliver, he seems to be someone who has grown up without a best friend.

A better comparison to Max & Carly is Australian Tim Winton’s 2008 novel Breath. In fact, the coincidental parallels are are nearly, well, breathtaking. As with my book, it is set in the 1970s and the focus of the story is a strong, nearly desperate, friendship between two boys in the backwater of Australia’s western coast. The dynamic between Bruce Pike, the only son of a modest and conservative couple, and Ivan Loon, the wild son of a feckless father, is much like that of Dallas and Lonnie. In fact, given the nicknames of Winton’s pair, Pikelet and Loonie, I found myself working hard not to read Loonie as Lonnie. What binds the two is their mutual love of surfing and the need to test their courage against bigger and bigger waves. They fall in thrall to Sando, a onetime surfing legend now living in self-imposed obscurity with his taciturn young American wife. For the most part, the book is a really good read, although I found the final chapters a bit of let-down. Pikelet narrates the story from the perspective of middle age, and the rapid encapsulation of his (mostly depressing) later life is an unwelcome turn after the high spirits of the earlier sections. Overall, though, it is a very good evocation of being young and male, having and losing a close friend, falling in love and getting on with the not-always-easy business of adult life.

The film adaptation of Breath is directed by Tasmania-born Simon Baker, who also plays the role of Sando. He is probably best known to U.S. audiences, who may not even realize he is not American, as the star of the long-running detective show The Mentalist.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)